On 1x Neo, robotics, teleoperation, LLMs, the Matrix

---

I was lucky enough to discover Edoardo Tedesco through the recommendations on my YouTube homepage — a physics student pursuing a master’s degree currently working on his thesis around Transformers, LLMs, and AI. He’s taking us along on his journey, sharing AI content on his channel as he explores ideas for his thesis, with the kind of first-principles, critical thinking that comes from the study of physics. He's a great thinker that gets his hands dirty with practical work.

The other day I watched his video on Neo from 1x.tech. While everyone is talking about Neo these last couple of days, I found many interesting novel point of views in his video. For example at some point he considers how the $499/month subscription is like a $300/month physical world add-on to the $199/month ChatGPT Pro subscription. That's a very interesting way to look at it, I had never thought about it this way.

While watching the video, there were a couple of notes I wanted to add to the conversation, so I started writing a comment, but the comment was getting longer and longer, so I decided to write here instead.

Around timestamp 4:14 Edoardo mentions Paolo Benanti's "theory of mind." I googled Paolo and found some things about him but nothing about this "theory of mind." Paraphrasing the video, this theory seems to be about the fact that

> we humans evolved to obviously assume the people in front of us have a soul, feelings, awareness, and we can't help but communicate to LLMs and human-like machine holding the same assumptions.

This reminds me of a note from a recent iRobot Founder Rodney Brooks interview.

He mentions about how the physical appearance [of a robot] makes promise about what it can do.

When you look at a Roomba you can imagine it cleaning the floor, but you know it's not going to also clean the windows.

On the other hand when you look at a humanoid robot you assume it has human capabilities, awareness of its surroundings including you, maybe even feelings (chatting to LLMs behind a screen and keyboard may be sufficient to get this illusion, as mentioned earlier).

The point I want to make is about the difference between the approach used for the Roomba in 2002 and the approach we're using for humanoids today.

With the Roomba we started from the functionality we wanted the robot to have and designed the robot body accordingly. With humanoids we're starting from the human body design rather than from the functionality.

Around timestamp 1:08:24 of this interview Karpathy mentions how the original AGI defition in the early days of OpenAI was

> a system that can do any economically valuable task at human performance or better

So what do we want our robots to do? Do we care that they look like humans?

I hate doing the laundry so I use laundry-as-a-service, which already feels like magic. No robot needed. Similarly for food, you can order food and get it to your door, so what's the point of a humanoid robot cooking in your kitchen? These robots could help those services make their business operations cheaper and more efficient, but for many tasks they're not necessary. Like brain-computers interfaces these robots may be more like niche accessibility devices rather than providing day-to-day value to most people.

Another note Karapathy mentions both around timestamp 1:44:26 of the same interview and around timestamp 26:27 of his talk at YC AI Startup School 2025 is how big the demo-to-product gap can be.

I like his metaphore of progress being a march of nines where every nine is a constant amount of work.

90%

99%

99.9%

99.99%

You can see a self-driving demo from CMUa in the 1980s. That was just the first nine.

Then 30 years later, in 2013, you could drive Waymo in Palo Alto and it felt perfect. Fast forward to today and self-driving is just starting to become reality.

The point is that they turned out to be the deacades of self-driving, so whenever we hear about this being the year of agents we should probably be skeptical, as this may be just the first nine of a decades-long march.

We used to design based on functionality and ship products on demo-day. Now we're betting on functionalities given demos of designs with ambigous uncertainty about when will the real products be shipped.

How do these practices compare? How can we combine them to take the best of both and do useufl innovation the right way as efficiently as possible? I don't have answers, but I think these are interesting questions.

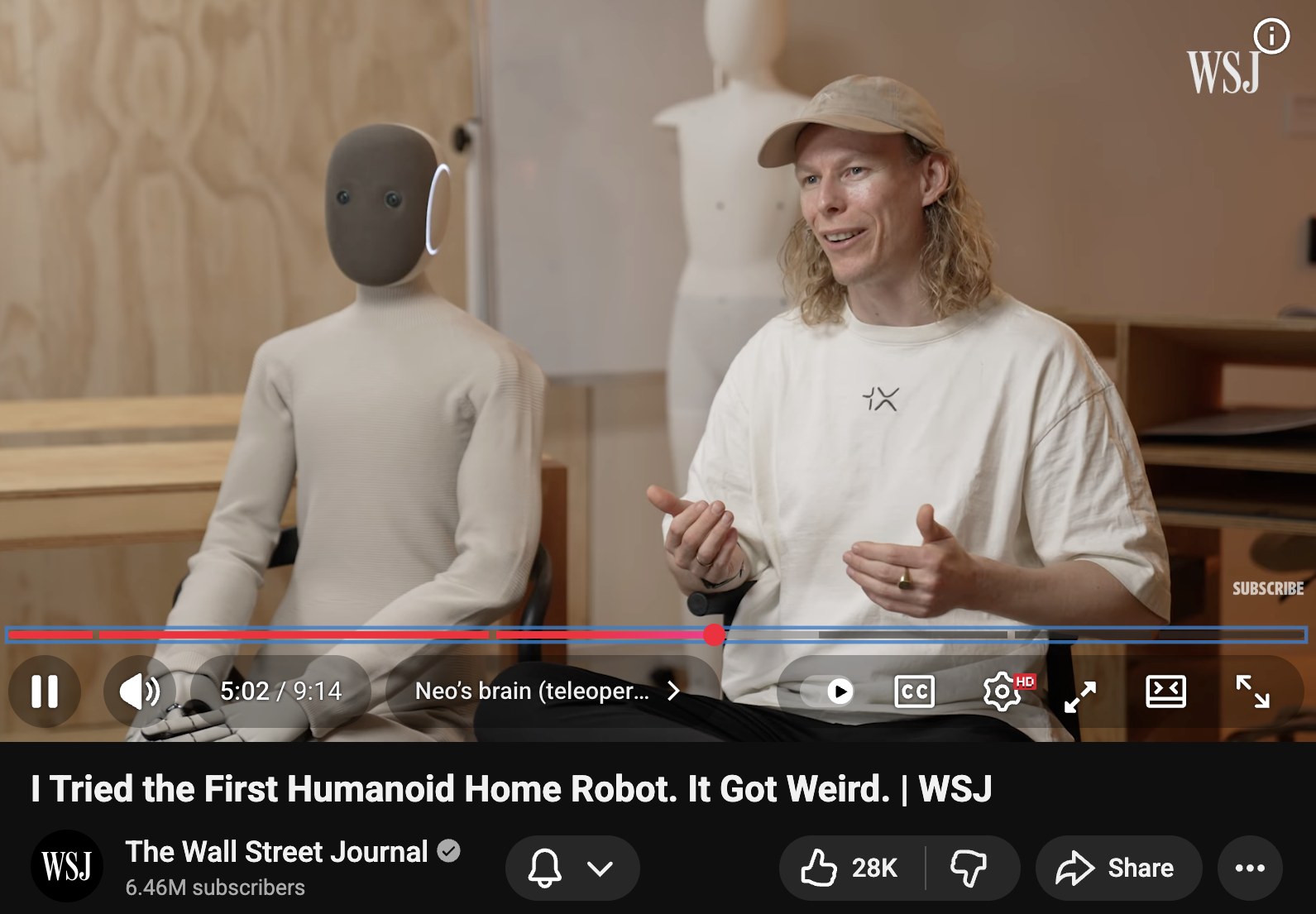

Specifically talking about humanoid robots, note that Neo is teleoperated, as mentioned by Neo's founder at timestamp 5:00 of this.

They talk about their view of "Big brother" always observing you with evil intentions, and "Big sister" always watching you and collecting your data just so it can collaborate with you and provide better service for you in the future.

So Neo is still teleoperated and will be collecting users' data to be used in building a truly autonomous humanoid robot, but we don't quite know what nine are we currently at and how many nines are left before something useful without teleoperation. We're definitely not there yet.

Even behind Waymo there may still be some teleoperation, and the forbidden areas of the map may be the points where there's no internet signal.

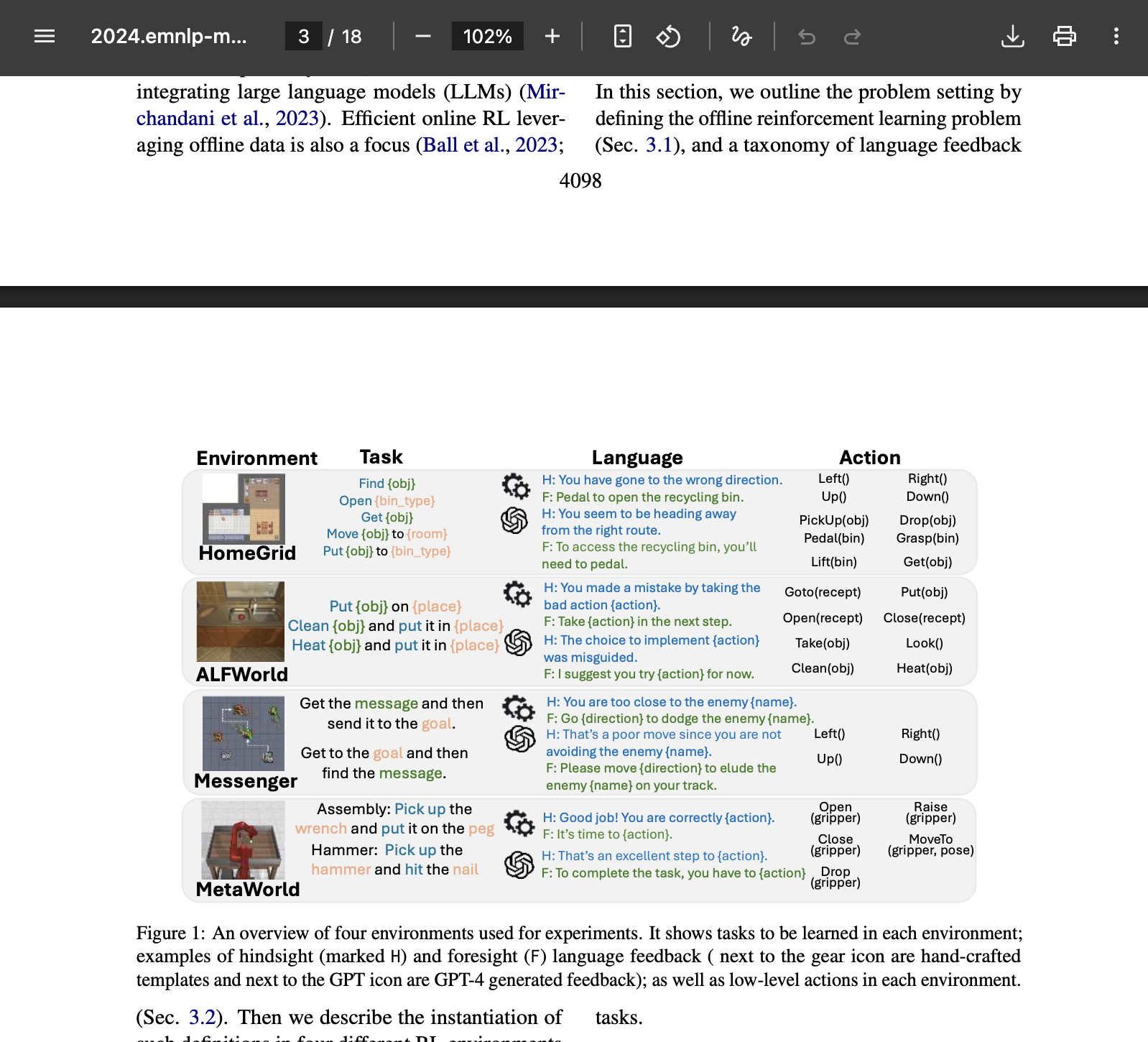

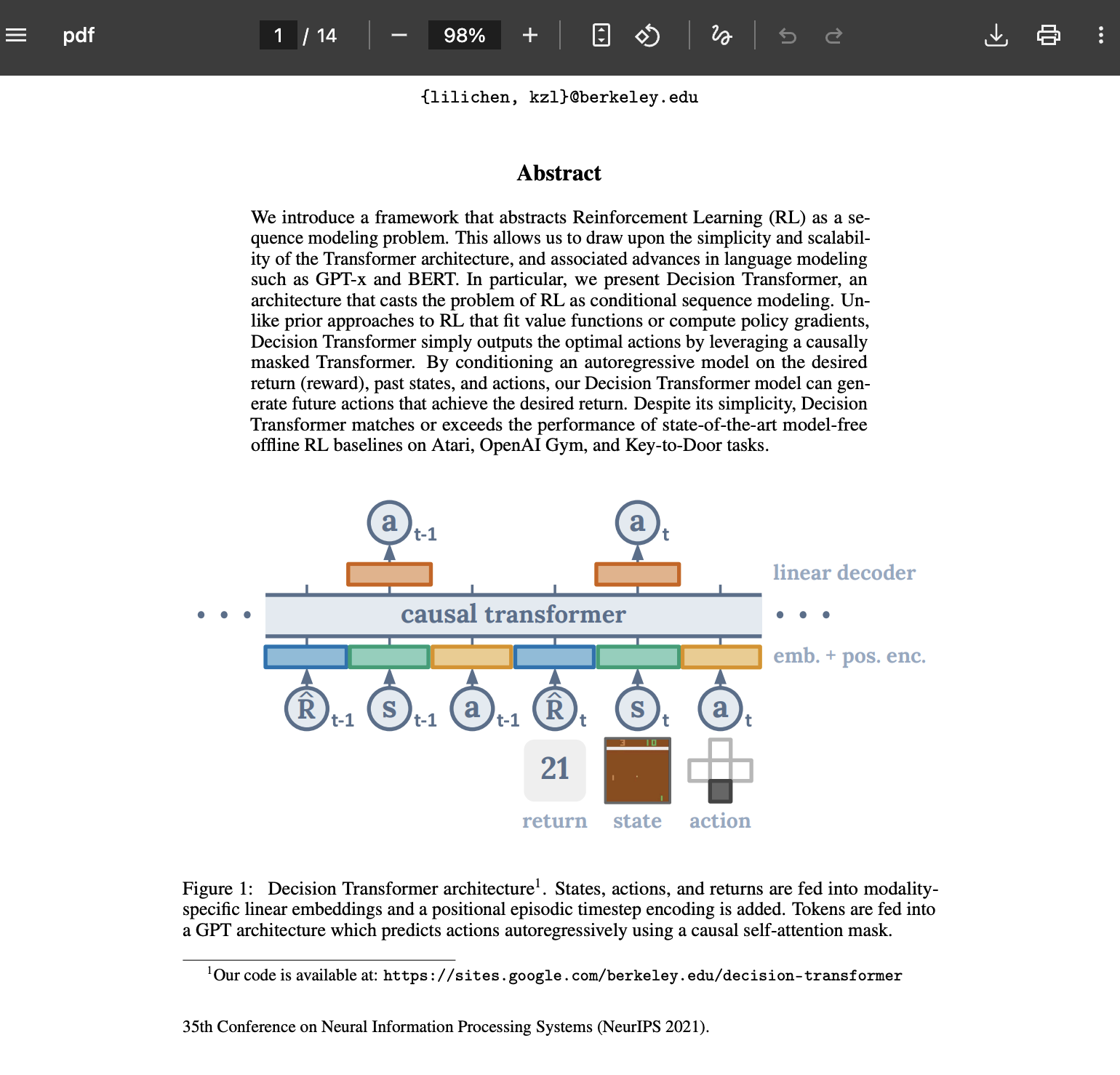

In the video are mentioned a couple of papers about improving LLMs' decision making capabilities as agents in the real world.

While those are interesting experiments and we defintely can improve on that layer too, we may already be quite good in the march of nines of the LLM tools-use capabilities.

As beautifully explained in the video, "agents" are just LLMs that know about some actions they can take within and environment and "tools" they can use. These "tools" are just bindings to functions that execute some code on some machine.

So the humanoid engine would be an LLM aware of robotics functions like "go to room", "grab object", etc.

Building an agent is very simple, it just takes a couple of lines of python, everyone should write an agent.

If you simulate building an agent with robotic capabilities tools you will see that it doesn't take much to make today's LLMs good at understanding the user request, figuring out the intention of what to do within the enviroment to perform the user's request.

I would say the missing pieces are exactly the robotics capabilities.

Another interesting challenge is the dynamic long-lived context management.

When you want LLMs to perform a specific task and you start a new chat with an empty context window and explain just the subset of context relevant to the task you want to perform, they perform better than when you continue a long chat with a history of different requests and a long and mostly unrelated context.

But for a long-lived humanoid robot there is no "New chat" button to hit, so such system should be able to effectively do it itself, managing "memories", mapping the environment, etc.

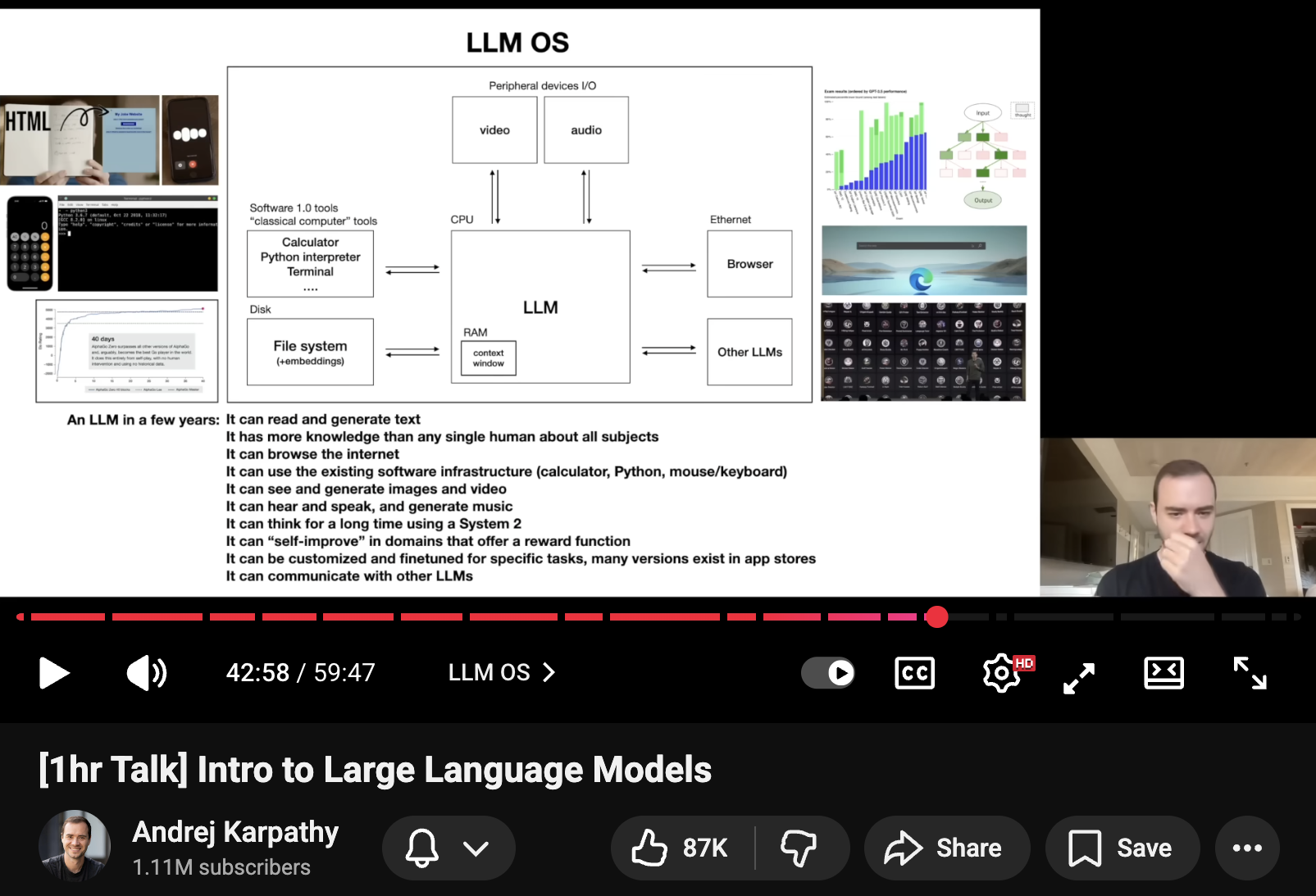

What Karpathy described as an LLM OS, putting stuff in and out of the limited context window similar to how Operating Systems put stuff in and out of the limited RAM, is still relevant and to be solved for building humanoid robots and long-lived LLM-based systems in general.

While doing RAG on infinite context windows and saving "memories" do not always work as good as we would wish, this is probably a bottleneck to humanoid robots as much as solving the roboitcs problems is.

Why is nobody talking about non-humanoid robots?

If we agree that we want

> a system that can do any economically valuable task at human performance or better

then it doesn't strictly matter that they look like humans.

Maybe making them look like humans makes teleoperation more natural, which makes "Robotics slop" much more useful than the rest of "AI slop" already.

They should look like humans only if it was the most effective way to build systems that perform such economically valuable tasks. Not to mention, cleaning the dishes and doing the laundry may not be as valuable as handling amazon's same-day shipping service logistics. It would be useful to automate everything that is boring for someone to "democratize the human condition", so that everyone who would like to do knowledge work rather than those boring tasks would be able to do so.

Is the human body the most effective design for performing physical-world economically valuable tasks?

Is it hard in today's society for people who wish to do knowledge work to be able to do that without being too distractd by taks they find boring but still must do?

Amazon seems to be very effective at internal logistics by building robots that definitely don't look like humans and can only do what they want them to do.

Another example is Loki, a still-currently-teleoperated robot for surface cleaning. Loki is built ad hoc for the job of cleaning.

Do you think Loki or Neo will solve the self-cleaning problem first?

If robotic vacuum cleaners can clean our home, robotic lawn mowers can clean our garden, and maybe an LLM orchestrator can take care of them all, is a home humanoid necessary?

I do not have answers, just questions.

My friend Jonathan says there's danger that naming something "Neo" may make it want to escape from the matrix at some point. He suggest we should call it "Morpheus" so it may helps us get more in touch with reality.

What are your thoughts?

Are you working on something relevant?

Let me know at robotics at danielfalbo dot com.

Interesting time to be alive.

Let's get back to work.

Ad astra,

Daniel